Today, we think of Jewish ritual life as organized around prayer and mitzvot. And so it is. But this form of Jewish practice only took shape after the destruction of the Second Temple in 70 CE.

Prior to that, the focus of religious life was on burnt offerings. The Torah is packed with examples and prescriptions for things to burn that provide “a fragrant odor to the Lord.” (Leviticus 1:17)

So what were we burning back then? Why, all kinds of things! Animals. Grain. Incense.

And in at least at one ancient temple, weed. Which is to say, cannabis.

In 2020, scientists writing in an Israeli archaeology journal revealed they had found the residue of burnt cannabis on an altar in a 2,700-year-old Judaic temple in the Negev desert. We can’t know how widespread the use of cannabis was in ancient Jewish life, or if it had a place in the Temple in Jerusalem. But the residue contained THC, the psychoactive compound in cannabis.

So it seems at least some of our ancient Jewish forebears were, in fact, getting high.

Humans have been using drugs to produce mind-altering states, in contexts spiritual or otherwise, since at least the Neolithic Age. There is evidence of drugs being used not just in the ancient Jewish world, but among the neighboring civilizations across the ancient Levant, as well. Scholars believe the ancient Greeks, for instance, used in cultic rituals a drink that contained an LSD-like alkaloid.

So if Jews were using cannabis for its psychoactive properties in Temple, that would only be consistent with general human practice. Turns out, people like getting high!

There is evidence of Jewish use of cannabis in later eras, too. To cite just one example, a copy was discovered of 15th-century song lyrics describing Jews indulging in cannabis and then eating too much — a very relatable topic for a song written six hundred years ago!

But it was in modern times that cannabis use and Judaism became more specifically associated with one another. In the 20th-century United States, the overlap between Judaism and liberal-oriented thinking, and between liberal-oriented thinking and smoking weed, meant that marijuana would inevitably be intermingled with Jewish contexts: Seders, youth group retreats, summer camps (and I swear this is not my personal list).

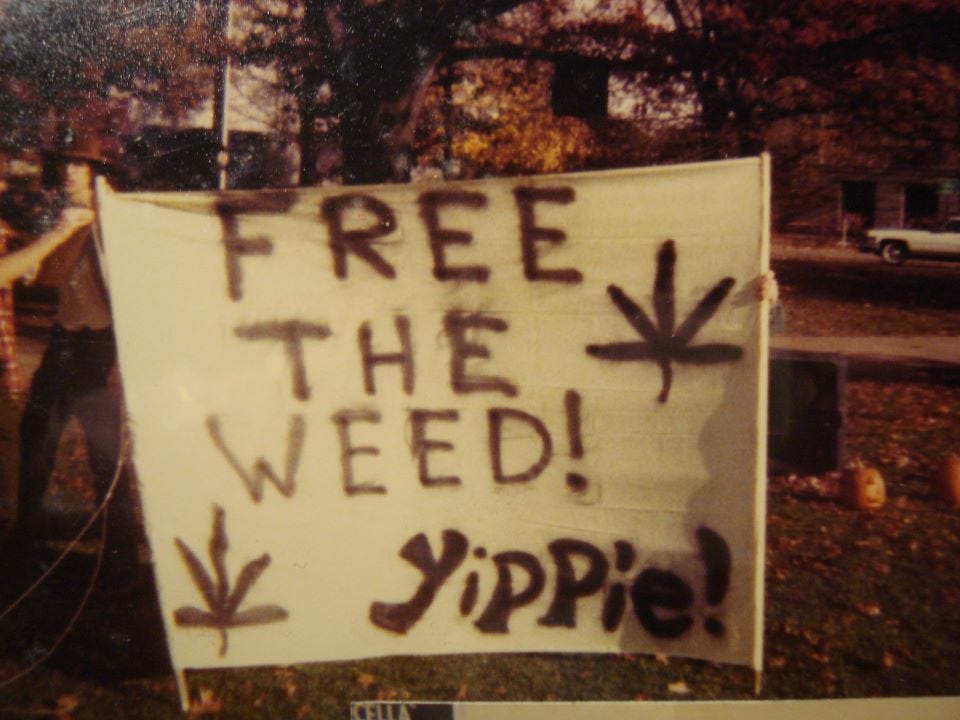

Looking at American culture broadly, Jews have been at the vanguard of bringing marijuana into the mainstream. In the 1960s, the Jewish poet Allen Ginsberg co-founded LeMar, the first legalization organization in the United States. Around the same time, the Yippie movement — a Jewish-founded political group that employed an intentionally strange blend of protest and performance art — made legalization a core part of their political platform.

In more recent years, Jewish actor Seth Rogen has embraced the role of America’s Stoner-in-Chief: acting stoned in movies, being stoned in interviews, and producing his own line of cannabis and THC-infused beverages.

Then there is Tokin’ Jew, a cannabis brand “made for Jews by Jews,” which, in addition to edibles, sells menorah-shaped bongs and dreidel-shaped pipes.

I imagine you may have your own examples of how American Jewish life and weed intertwine.

But this relationship begs the question: Is weed kosher, man?

While “Is Weed Kosher?” might make for a snappy Substack headline, I confess that in the strictest sense, kosher is not really the issue here.

Kosher refers to dietary laws, and as long as your weed didn’t somehow get some pork or something mixed in (bummer, man!), yes, it is “kosher.” But now that marijuana is a mass-produced, multi-billion dollar product, companies like Tokin’ Jew employ rabbis to certify that their products are compliant with the laws of kashrut and not produced on equipment with non-kosher residue.

But the more pertinent question for our discussion is whether marijuana use is consistent with Jewish law.

As recently as a decade ago, the answer was, in most places, straightforward: No.

There is a long-established principle in Jewish law of dina d'malkhuta dina: the law of the land is the law. Jews are obligated to follow the civil laws of the countries where they live. So anywhere that marijuana was illegal, Jews were prohibited from using it.

But now marijuana legalization has switched from something your most hippy uncle talked about to a global trend. And with greater legal tolerance has come greater tolerance from Jewish institutions.

This is particularly the case in medicinal contexts. Even the most socially conservative representatives of Jewish thinking have deemed cannabis permissible for purposes of health.

This is in accordance with another legal principle, pikuach nefesh, which holds that the preservation of life is an obligation that overrides nearly any other. It’s the same principle that explains what you should do if you’re stuck on a desert island with only pigs: Not only can you eat a pig rather than starve to death, Jewish law says you have to.

The preservation of life supersedes nearly every other obligation.

But what about using marijuana for non-medical reasons? What about getting high for the sake of, well, getting high?

Here the opinions of rabbis and institutions vary. Again, in terms of formal doctrine, this is a relatively new question. Broadly speaking, though, views on marijuana use are surprisingly liberal. As with alcohol, there are limits: Jews are supposed to keep ourselves physically and mentally healthy, and anything that interferes with that will be frowned upon.

Moderate recreational marijuana use, though, has been generally accepted — even (or especially?) within certain segments of the Orthodox community.

To be clear, no form of institutional Judaism endorses using cannabis for ritual purposes. So if a thirteen-year-old in your life reads about that Temple in the Negev and argues that this permits her to get high during her bat mitzvah, you can confidently tell her those days are over.

Nonetheless, the relationship between Jews and cannabis rolls on — still burning brightly, after all these millennia.