Before superheroes took over popular culture, they were the invention of Jewish creators who couldn’t get work in the conventional publishing industry.

Talented Jewish immigrants and the children of immigrants in the 1930s and ‘40s, shut out of the clubby (read: antisemitic) mainstream publishing world, took their imagination, art, and storytelling powers to the cheap, low-status world of comic books.

And just like the Jewish innovators behind Barbie (Ruth Handler) and Broadway (Irving Berlin, the Gershwins, Leonard Bernstein, Stephen Sondheim), these creators elevated their art forms and left an indelible mark on American life.

Jewish writers and artists dreamed up almost the entire litany of iconic superheroes: Batman (Bob Kane and Bill Finger), Captain America (Joe Simon and Jack Kirby), Spider-Man (Stan Lee and Steve Ditko), the X-Men and the Hulk (Lee and Kirby), and Doctor Strange (Lee and Ditko).

The whole notion of a superhero as we understand it — a crusader for justice with a secret identity — is a Jewish invention.

And thanks to the blockbuster new movie, there is no superhero currently more popular, more ubiquitous than the first one of them all: Superman, the 1938 brainchild of Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster, two children of first-generation Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe.

Superman is everywhere right now. And he’s Jewish!

I don’t just mean that David Corenswet, the actor who plays Superman in the new movie is Jewish. He is, and that’s great!

I mean that Superman is Jewish.

Okay, he is not canonically Jewish. The Jews working in the early comics industry almost never made their characters explicitly Jewish: This would have been a dicey commercial proposition in the ‘30s and ‘40s (or, let’s face it, in many of the decades that followed, not excluding this one). Superman never dons a yarmulke and goes to services and then leaves before oneg to save Metropolis.

But even so: Superman is Jewish. Not just by dint of his creators, not just because his name ends in -man, not just because Clark Kent actually looks Jewish, at least as he is portrayed by Siegel & Shuster…

Superman’s Judaism is found most strongly in the ways he manifests the Jewish American experience: the legacy, the hopes, the feelings of alienation, the feelings of obligation.

There are plenty of antecedents for the idea of a super-powered do-gooder in the Jewish tradition.

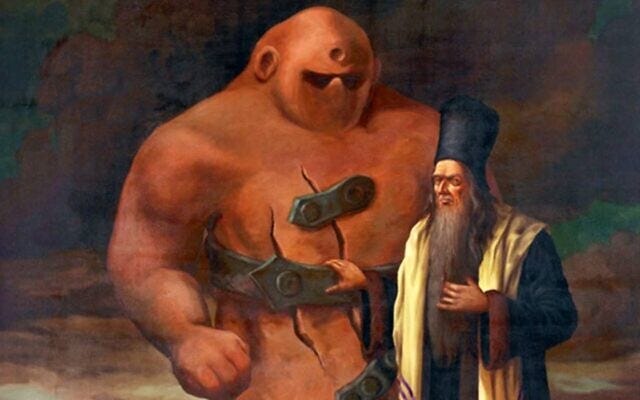

Moses is saved via a basket in the Nile, a lot like how Superman is saved via a rocket to Earth. And if you’re not reading closely, you could easily conclude that between the plagues and the Red Sea, Moses employs some pretty remarkable superpowers in delivering the Israelites from bondage. Then there’s Samson, with the strength to kill a thousand Philistines with the jawbone of an ass. And millennia later, we have the legend of Rabbi Judah Loew ben Bezalel creating the mighty Golem to defend the Jews of Prague.

In all these tales, we see the Jewish people threatened by tyranny, violence, and antisemitism, and being delivered by the actions of a heroic figure with preternatural gifts.

It’s not hard to see why this idea would appeal to the Jews of Siegel and Shuster’s generation, writing against the backdrop of Nazism in Europe.

Maybe it helps explain Superman’s renewed appeal to us, too.

Based on the box office receipts, it seems the notion of a superhero delivering the world from injustice remains resonant with the America of 2025.

To me, though, the most compelling Jewish source for the comic book superhero is Esther.

Not just for her heroism — which is considerable, given that she saves the Jewish people from genocide — but because of her dual identity.

As the Megillah read on Purim tells us, when Esther becomes queen, she hides her Judaism. Which is to say, she has a secret identity. But in the hour of the Jewish people’s greatest need, she reveals who she truly is in order to save the day.

You can draw a straight line from Esther to Clark Kent/Superman.

But living with a dual identity is hardly exclusive to ancient Persia or the panels of a comic book. It’s an experience familiar to the millions of American Jews.

First-generation Jewish immigrants, like Superman, had to navigate the psychological gulf between the Old World and this new one. And even Jews who have spent their whole lives here may know what it’s like to walk around dressed anonymously as Clark Kent — but then putting on a tallit and a kippah in the service of another dimension of identity.

Not that you have to wear a yarmulke to feel your sense of difference from America’s religious and cultural norms. Like Esther or Clark Kent, we might not always be recognizable for our true identity.

But it’s not like we ever forget.

And that Jewish identity brings with it its own particular obligations.

Judaism teaches that we have a special responsibility to attempt, in whatever way we can, to repair the world, to leave it at least a little better than we found it.

So Superman’s determination to be, as Siegel and Shuster put it back in 1938, a “champion of the helpless and oppressed,” part of an “unceasing battle against evil and injustice” might be the most Jewish thing about him.

There’s actually a sequence late in the new movie where Superman tries to stop a crack from tearing apart the Earth. He’s doing literal tikkun olam!

And people say this guy isn’t Jewish!

But in the end, of course, superheroes are fiction — ink on newsprint, CGI on a screen. No one is going to come flying out of the sky to rescue us.

So if the world needs saving — and man oh man, it feels like it does — we’re going to have to be the ones to do it.

Love this one! Forwarded it to my son :)